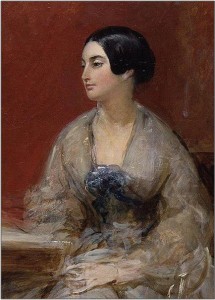

Caroline Norton: wronged wife, heroine of English Laws for Women; novelist, poet, mother, wit and political lobbyist. We end our series with a personal heroine, a woman whose general neglect by historians is as amazing as it is heinous. Caroline was born into a family of three girls known as the Graces, dazzling grand-daughters of the Irish Whig playwright Richard Sheridan. Politics and London’s elite society were in their blood. London adored them.

Caroline’s disastrous marriage to the boorish, stupid and grasping George Norton, whose family were implacable snobs and Tories, set in train a saga which spans that crucial period of English history from 1830 to 1850 when reform and reaction in Britain and across Europe created an extraordinary febrile atmosphere of intrigue, energy and style. These were the first years of Victoria: of the Great Reform Bill and Chartism, of the Pre-Raphaelites and the Railway Age; but also of poverty, factories, injustice and sobriety.

Caroline knew everyone. For a while her scandalous association with Prime Minister Lord Melbourne (former husband of Lady Caroline Lamb) threatened to wreck his career and bring down his government. It nearly destroyed Caroline. But the deliberate estrangement of her children by the dastardly George fired her to campaign for the rights of all women and mothers. Her legacy is profound and lasting.

From Caroline Norton’s A Voice from the Factories 1836

Beyond all sorrow which the wanderer knows,

Is that these little pent-up wretches feel;

Where the air thick and close and stagnant grows,

And the low whirring of the incessant wheel

Dizzies the head, and makes the senses reel:

There, shut for ever from the gladdening sky,

Vice premature and Care’s corroding seal

Stamp on each sallow cheek their hateful die,

Line the smooth open brow, and sink the saddened eye

Letters from Lord Melbourne to Caroline 1836

Every communication elates him and encourages him to persevere in his brutality. You ought to know him better than I do, and must do so. But you seem to me to be hardly aware what a gnome he is, how perfectly earthly and bestial. He is possessed of a devil, and that, the meanest and basest fiend that disgraces the infernal regions…

I have never mentioned money to you, and I hardly like to do it now; your feelings have been so galled that they have naturally become very sore and sensitive, and I knew how you might take it. I have had at times a great mind to send you some, but I feared to do so. As I trust we are now upon terms of confidential and affectionate friendship, I venture to say that you have nothing to do but express a wish, and it shall instantly be complied with. I miss you. I miss your society and conversation every day at the hours at which I was accustomed to enjoy them; and when you say that your place can easily be supplied, you indulge in a little vanity and self-conceit. You know well enough that there is nobody who can fill your place.

Submission to Parliamentary debate on her Matrimonial Causes Act 1857

An English wife may not leave her husband’s house. Not only can he sue her for restitution of “conjugal rights,” but he has a right to enter the house of any friend or relation with whom she may take refuge…and carry her away by force… If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself… She is not represented by attorney, nor permitted to be considered a party to the suit between him and her supposed lover, for “damages.” If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband, a vinculo, however profligate he may be…. Those dear children, the loss of whose pattering steps and sweet occasional voices made the silence of [my] new home intolerable as the anguish of death…what I suffered respecting those children, God knows… under the evil law which suffered any man, for vengeance or for interest, to take baby children from the mother.

Caroline Norton Timeline

1808 Caroline Sheridan, grand-daughter of Richard, born

1817 Father Thomas dies in S Africa as colonial administrator; family penniless

1827 Caroline, aged 19, marries George Norton Tory MP for Guildford – to 1830

1829 Caroline has first child, Fletcher; The sorrows of Rosalie appears anonymously

1830 William IV accedes: General election won by Whigs. New Home Secretary

Lord Melbourne meets Caroline; George Norton loses seat; Caroline begs

Melbourne for job; George given judgeship of police courts worth £1,000 a

year; Caroline writes The undying one

1831 Second son Brinsley born

1832 Caroline takes up editorship of La belle assemblee and court magazine

1833 Great Reform Bill passed; C encourages Charles Babbage to stand for MP

1834 The Nortons’ marriage breaks down; Caroline Norton the English Annual

1835 Nortons split and are uneasily reconciled; Melbourne becomes Prime Minister:

rumours of affair with Caroline;

1836 Norton adultery case against Lord Melbourne; Norton loses

Caroline writes: A voice from the factories; The wife and woman’s reward

1837 C. Separation of mother and child by the custody of infants considered

1838 George Norton takes children to Scotland

1839 Infant Custody Act passed; Caroline publishes: The Dream and other poems

1841 Caroline finally sees her boys, for Christmas

1842 Caroline’s youngest son William dies from tetanus

1845 Caroline Norton: The child of the islands

1848 Caroline Norton: Letters to the Mob

1851 Caroline Norton: Stuart of Dunleath

1854 Caroline Norton: English laws for women in the 19th century

1857 Matrimonial Causes Act passed

1859 Fletcher dies of tuberculosis in Paris, aged 30

1877 Caroline marries Sir W. Stirling Maxwell; Caroline dies

1885 Diana of the Crossways by George Meredith

Reading

Caroline Norton by Alice Acland 1948. Constable. London